The Kabbalah of the Bean

“It’s a drink the ultra-Orthodox lack,” said Kfir Cohen, the Israeli businessman behind the brew, which consists of 58 different extracts and was developed over 18 months at a cost of $500,000 (£250,000).This news story about a kosher energy drink reminded me of an article I read a while back. I am not sure who wrote it originally, but I found an unattributed copy on the Web.“There are three things going on here. They make a lot of babies, they study the Torah and they dance. They need a lot of energy, and something to strengthen them.”

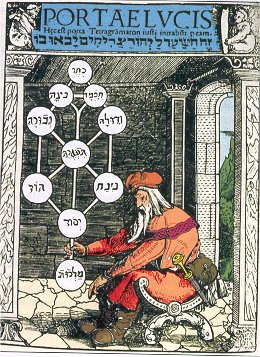

The Influence of Coffee on Kabbalistic

All-Night and Midnight Vigils

One of the innovations of Lurianic Kabbalah was the creation of a variety of rituals which took place late at night. Joseph Karo is credited with the creation of the all-night study session on the eve of Shavuot, called Tikkun Leil Shavuot. The Ari himself emphasized the importance of prayer and meditation late at night (called Tikkun Chatzot or Tikkun Rachel) and early in the morning (called Tikkun Leah). These times connected the individual with the daily creations of light and darkness. It also was an ideal time (according to the Zohar) to mourn the banishment of the Shechinah from Jerusalem. It also connected the individual with King David, who was said to have created the Psalms at midnight. The powerful image that the gates of Heaven are most available for prayer late at night was thus concretized in Tzfat in the late 16th century. Ironically, it didn’t catch on in Jerusalem at the same time even though Jerusalem mystics were certainly aware of the Zohar’s emphasis on midnight and all-night vigils. Jerusalem’s mystics focused on pre-dawn rituals instead.

Elliott Horowitz provides us with a fascinating thesis about the creation and development of late-night and all-night rituals as opposed to early morning rituals in 17th-18th century Jewish mystical circles. He notes that coffee arrived in Tzfat in 1528, and the first coffee house appeared in Tzfat in 1580. None came to Jerusalem. The use of coffee as a stimulant might have encouraged the mystics of Tzfat to focus more on all-night and late-night rituals because they couldn’t sleep anyway. Karo’s Tikkun Leil Shavuot appeared two or three years after the introduction of coffee to Tzfat. Horowitz quotes the following description of Tzfat in 1587: (Abraham haLevi Beruchim) would rise at midnight and walk through all the streets, raising his voice and shouting bitterly, “Arise in honor of the Lord…for the Shechinah is in exile and our Temple has been burnt.” And he would call each scholar by his name, not departing until he saw that he had left his bed. Within an hour the city was full of the sounds of study: Mishnah and Zohar and midrashim of the rabbis and Psalms and Prophets, as well as hymns, dirges, and supplicatory prayers.”

By 1673, Tikkun Chatzot had become the known ritual for the vast majority of Palestinian Jewry, and Italian Jewry knew that most Palestinian Jews drank coffee before prayers. Coffee had not yet arrived in Italy. In the late 1570’s, Italian mystics created their own pre-dawn rituals. They called themselves Shomrim LaBoker, the Guardians of the Morning. These rituals were apparently initiated by kabbalists who were familiar with the midnight and all-night devotions of the Jews of Tzfat. They acknowledged that midnight was the best time for prayer “when God amused Himself with the righteous in the Garden of Eden,” but they were not willing to maintain the midnight tradition. Instead, they slept through the night and woke before dawn for their early prayers. At least seven editions of predawn liturgies were published indicating their popularity.

Coffee arrived in Venice in 1615. The first coffee house (making coffee available to the masses) opened in 1640. In 1655, a liturgy for Tikkun Chatzot was published in Italy and a Chatzot group was formed. In that same year (for the first time), Italian Jews accepted Joseph Karo’s ritual of Tikkun Leil Shavuot. However, coffee was not as popular in Venice as it was in Tzfat. By 1683, there was still only one coffee house in Venice, and there were few Jews drinking the exotic drink. By 1759, coffee-drinking had soared in Italy. There were more than 200 coffee houses in Venice, including two in the ghetto. Jews in Mantua were making a fortune in the coffee industry. A scandal resulted in a ruling that “women could not enter coffee houses whether by day or night.” The popularity of Tikkun Chatzot also rose impressively. By 1755, most pre-dawn prayer groups in Verona had become midnight and all-night prayer groups. The same thing happened in Mantua. The same thing happened in Modena and Venice.

Coffee arrived in Worms, Germany in 1728. By 1763 mystic circles were regularly celebrating midnight and all-night vigils for the first time.

In short, although the Zohar and kabbalistic works had always emphasized the special significance of midnight, ongoing prayers and all-night vigils did not become an important part of Kabbalistic life until the introduction of coffee into each Kabbalistic community. Today, midnight and all-night prayers remain an important part of Kabbalistic ritual, and many Jews continue to stay up all night on Shavuot and meet for supplication prayers at midnight on Selichot. Our level of caffeine stimulation makes our participation in such all-night rituals much easier.