More Morality Musings - Revenge Killings

In 1992, when Daniel Wemp was about twenty-two years old, his beloved paternal uncle Soll was killed in a battle against the neighboring Ombal clan. In the New Guinea Highlands, where Daniel and his Handa clan live, uncles and aunts play a big role in raising children, so an uncle’s death represents a much heavier blow than it might to most Americans. Daniel often did not even distinguish between his biological father and other male clansmen of his father’s generation. And Soll had been very good to Daniel, who recalled him as a tall and handsome man, destined to become a leader. Soll’s death demanded vengeance.

Daniel told me that responsibility for arranging revenge usually falls on the victim’s firstborn son or, failing that, on one of his brothers. “Soll did have a son, but he was only six years old at the time of his father’s death, much too young to organize the revenge,” Daniel said. “On the other hand, my father was felt to be too old and weak by then; the avenger should be a strong young man in his prime. So I was the one who became expected to avenge Soll.” As it turned out, it took three years, twenty-nine more killings, and the sacrifice of three hundred pigs before Daniel succeeded in discharging this responsibility.

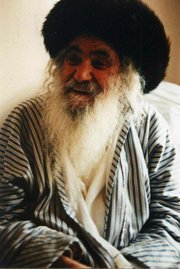

I first met Daniel half a dozen years after these events, while he was working for the Papua New Guinea branch of ChevronTexaco, which was then managing oil fields in the Southern Highlands, about thirty miles from Daniel’s home village. The fields, where I was doing environmental studies, lie in forest-covered hills near the beautiful Lake Kutubu. The weather is warm but wet—the region gets hundreds of inches of rain a year. As the driver assigned to me, Daniel picked me up an hour before dawn each day, drove me out along narrow dirt roads, waited while I jumped out every mile or so to record birdsongs, and drove me back to the oil camp in time for lunch. He was slim but muscular, and, like other New Guinea Highlanders, dark-skinned, with tightly coiled dark hair, dark eyes, and a strongly contoured face. From the outset, I found him to be a happy, enthusiastic, sociable person. During our hours together on the road, we enjoyed sharing our life stories. Despite some big differences between our backgrounds—Daniel’s Highland village life focussed on growing sweet potatoes, raising pigs, and fighting, and my American city life focussed on college teaching and research—we enjoyed many of the same things, such as our wives and children, conversation, sports, birds, and driving cars. It was in these conversations that he told me the story of his revenge.

Daniel’s homeland and other parts of the New Guinea Highlands have been of interest to anthropologists ever since the nineteen-thirties, when Australian and Dutch prospectors and patrols “discovered” a million stone-tool-using tribespeople previously unknown to the outside world, and began to introduce them to metal, writing, missionaries, and state government. Since then, changes have been rapid. When I first visited New Guinea as a scientist, in 1964, most Highlanders still lived in thatched huts with walls of hand-hewn planks, and many wore grass skirts and no shirts; now many huts have tin roofs and most people wear T-shirts and shorts or trousers. And yet Highlanders still inhabit two worlds simultaneously. Daniel’s loyalties are first to his Handa clan and to his Nipa tribe, and then to his nation of Papua New Guinea, which is attempting to weld its thousands of clans and hundreds of tribes into a peaceful democracy.

State government is now so nearly universal around the globe that we forget how recent an innovation it is; the first states are thought to have arisen only about fifty-five hundred years ago, in the Fertile Crescent. Before there were states, Daniel’s method of resolving major disputes—either violently or by payment of compensation—was the worldwide norm. Papua New Guinea is not the only place where those traditional methods of dispute resolution still coexist uneasily with the methods of state government. For example, Daniel’s methods might seem quite familiar to members of urban gangs in America, and also to Somalis, Afghans, Kenyans, and peoples of other countries where tribal ties remain strong and state control weak. As I eventually came to realize, Daniel’s thirst for vengeance and his hostility to rival clans are really not so far from our own habits of mind as we might like to think.

[Full article in the New Yorker]

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home