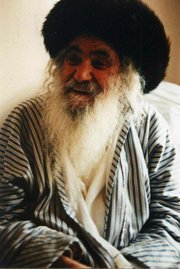

"...his books emit an odor of heresy"

Just read about the blacklisting of Rabbi Jose Faur in Wikipedia. A couple of highlights:

Controversy:

While teaching at JTS, Faur also offered Torah classes to members of the Syrian community in Brooklyn, New York. This aroused the opposition of certain circles of the right-wing Yeshiva world since they indentified him with the Conservative movement (to which denomination the Jewish Theological Seminary did indeed belong to).

Faur, however, received the support of the Chief Rabbi of the Syrian community, Rabbi Jacob Kassin who signed an open letter attesting to Faur's religious standing. Kassin explained that Faur did not agree with the Conservative movement at all and that he had only taught at the school in order to earn a living.

Lined up against him, however, were several high profile Haredi Rabbis from both the Sephardic and Ashkenazic communties, including Rabbis Moshe Feinstein, Ovadiah Yosef and Elazar Shach.

The pressure was such that Rabbi Kassin retracted his previous support and joined the campaign against Faur.

In the summer of 1987, Faur received support from an unexpected source. The Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem, Rabbi Chalom Messas convened a beit din which examined the allegations against Faur and came to the conclusion that he was innocent of all charges. Chief Sephardic Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu later affirmed the decision as well. But the controversy did not abate. The Lithuanian Yeshiva world's weekly Yated Neeman of February 8, 1998 carried an ad which called for the prevention of the appointing of a Conservative Rabbi to the Syrian congregation Shaare Zion in New York. Aside from his involvement with the seminary, the ad accused him of "speaking improperly about great medieval Ashkenazic sages and this his books emit an odor of heresy". The declaration was signed by 17 Sephardic heads of Yeshivot. Again, under intense pressure, Rabbis Messas and Eliyahu withdrew their earlier support.

Faur reminisces about his time at the [Lakewood] Yeshiva:

"The first lesson I heard by Rabbi Kotler sounded like a revelation. He spoke rapidly, in Yiddish, a language I didn't know but was able to understand because I knew German. He quoted a large number of sources from all over the Talmud, linking them in different arrangements and showing the various inerpretations and interconnection of later Rabbinic authorities. I was dazzled. Never before had I been exposed to such an array of sources and interconnections. Nevertheless there were some points that didn't jibe. I approached R' Kotler to discuss the lesson. He was surprised that I had been able to follow. When I presented my objections to him, he reflected for a moment and then replied that he would give a follow-up lesson where these difficulties would be examined. This gave me an instant reputation as some sort of genius (iluy), and after a short while, I was accepted into the inner elite group. My years in Lakewood were pleasurable and profitable.... At the same time the lessons of R' Kotler and my contacts with fellow students were making me aware of some basic methodological flaws in their approach. The desire to shortcut their way into the Talmud without a systematic and methodological knowledge of basic Jewish texts made their analysis skimpy and haphazard...The dialectics that were being applied to the study of Talmud were not only making shambles out of the text, but, what was more disturbing to me, they were also depriving the very concept of Jewish law, Halacha, of all meaning. Since everything could be "proven" and "disproven", there were no absolute categories of right and wrong. Accordingly, the only possibility of morality is for the faithful to surrender himself to an assigned superior authority; it is the faithful's duty to obey this authority simply because it is the authority and because he is faithful. More precisely, devotion is not to be measured by an objective halacha (it has been destroyed by dialectics) but by obedience. Within this system of morality there was no uniform duty. It was the privilege of the authority to make special dispensations and allowances (hetarim) to some of the faithful; conversely, the authority could impose some new obligation and duties on all or a part of the faithful. To me this was indistinguishable from Christianity".

4 Comments:

Oooh, interesting. Since when did you become Missisipi Fred McDowell?

Since he stopped posting...

What does heresy smell like and can dogs be trained to follow it? This is halacha l'maaseh. ;-)

>What does heresy smell like

I am not sure, but there's always the "aroma of Christ"!

Post a Comment

<< Home